Cross-border

economic

development

10

Preamble

The “presential” economy

This view leads to a different way of envisaging public action with

respect to the economic development of a territory, which is no

longer focused solely on developing existing firms and attracting

new ones. An economic analysis of a territory must take into

account the links between the different spaces that people operate

in (home, production, consumption and leisure), connected by an

efficient transport system, and incorporate the potential constituted

by capturing the wealth available within the population present in

the territory: the development of service activities (retail and leisure,

and business and leisure tourism). The aim is then to develop a

welcoming strategy with regard to new residents, commuters and

tourists that helps to develop service activities

6

for the population,

thereby creating jobs that, by definition, cannot be relocated.

Each territory has a specific balance between productive and

presential economies that results from its particular geography

and history (productive and social capital, accessibility, amenities,

etc.). Some territories can “get along well” without a productive

economy. Of course, the viability of a territory’s economy depends

on exchanges with the world outside: in an open economy, the

goods and services produced need to find external markets; and

the flows that support the presential economy need to be fuelled by

revenue produced elsewhere (work of commuters and tourists, social

security benefits of the unemployed and pensioners, and the funding

of public services).

The territories based more or less on a productive or presential

economy support one another, with this solidarity being the result

both of the market itself and of public policies that redistribute

revenue between territories, whether explicitly (territorial

development) or implicitly (network of public services and social

security provision).

The regulation of this redistribution is primarily carried out by

national governments; it is currently the subject of intense debate

and far-reaching reforms in France and the neighbouring countries.

This not only raises the issue of social cohesion (level of social

security contributions and taxes, the trade-off between efficiency

and equality) but also that of territorial cohesion (the optimum

administrative level for public action, territorial equality, an approach

based on population or territory depending on the extent to which

residential mobility is encouraged).

In a context in which governments’ ability to ensure cohesion is

being curtailed by the crisis in public financing, L. Davezies recently

proposed the idea of “dual production-based and residential

systems”,

7

large territories that combine the two spheres, giving

them greater viability. It is the fact that some of these systems

are cross-border in character, whereas, so far, regulations remain

national, that makes cross-border territories laboratories for

European territorial cohesion.

6

http://www.insee.fr/en/methodes/default.asp?page=definitions/sphere.htm

7

L. DAVEZIES and M. TALANDIER,

L’Emergence de systèmes productivo-résidentiels.

Territoires productifs – Territoires résidentiels: quelles interactions ?

, CGET (General

Commission for Territorial Equality), La Documentation française, 2014.

Presential and

non-presential spheres:

the particular case of cross-

border territories

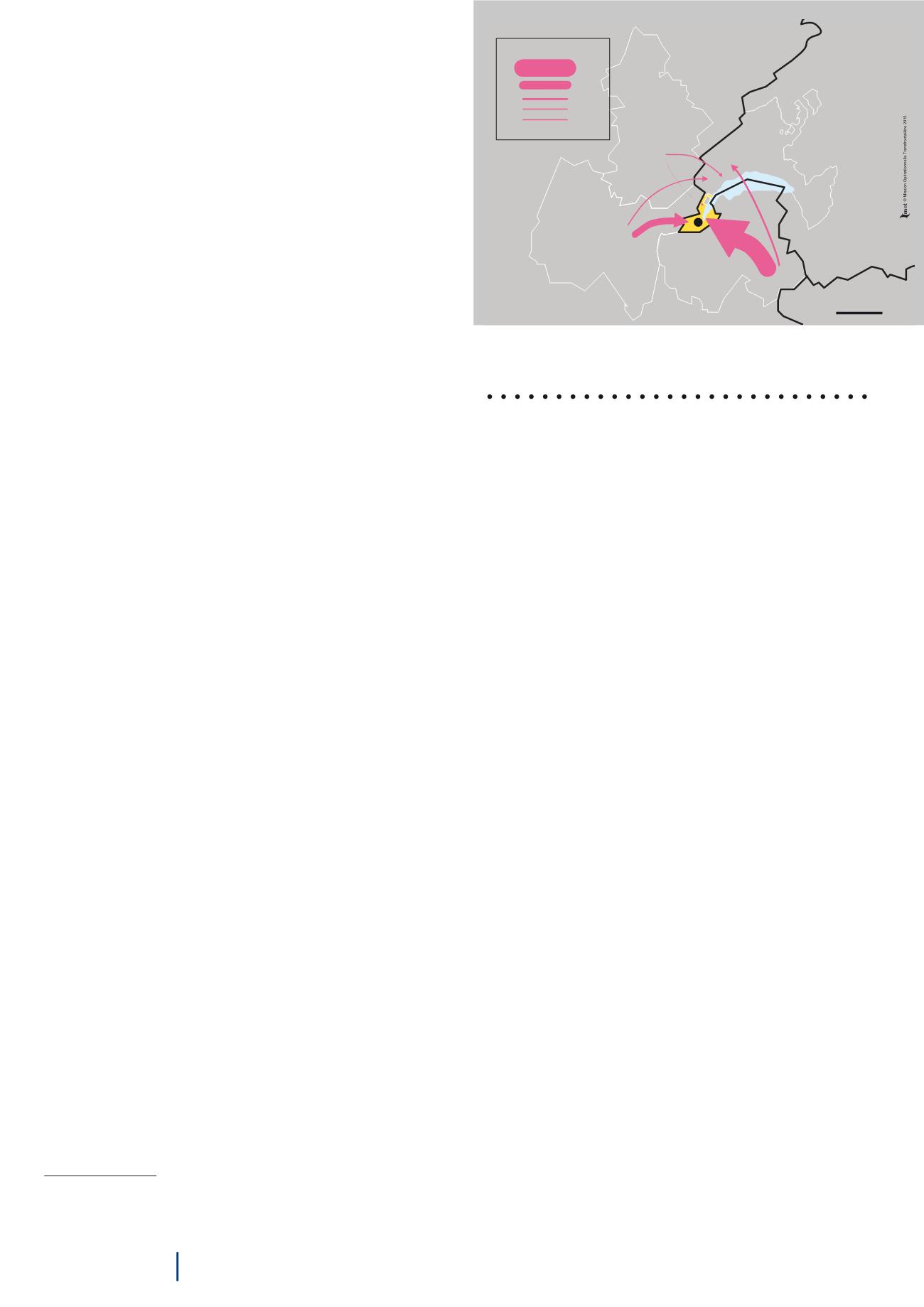

As in any territory, the two aspects (productive and presential) are present

in a border or cross-border territory. But sometimes the border serves

to separate a more “productive” area, with industries producing goods

and services that are not necessarily intended for the territory, from a

more “presential” area, in which the retail sector, tourism and services

to the population are more developed. Some French border territories

are emblematic in this regard due to the intensity of the home-work

flows of people crossing the border (to Luxembourg and the Basel and

Geneva conurbations from the surrounding territories).

The dichotomy between a predominantly productive territory and a

predominantly presential territory would, within a single State, be the

subject of various public means of regulation (spatial planning aimed at

rebalancing flows, financial solidarity, reorganisation of local government,

etc.), but such public policies are highly problematic in this case owing

to the fact that a national border divides the predominantly presential

territory from the predominantly productive territory.

A cross-border analysis is therefore important for this type of area,

particularly regarding the distribution of living spaces and of the provision

of services. This dimension of territorial planning is not always shared

in cross-border settings: this is where there is sometimes a divergence

in the role of public intervention to promote economic development.

Even if not all borders display such a polarisation, the movement of

people, goods, services and capital, and as a result, the integration of

territories, no longer takes place just within each country, but within

the European area as a whole (the European Union and third countries

such as Switzerland). The hypothesis of this research is that this mobility

plays or can play a more significant role in the context of cross-border

regions, where it is a potential source of prosperity, if it is regulated in

a coordinated manner by the countries on either side of the border.

100 km

VAUD

Jura

Ain

FRANCE

Number of cross-borderworkers

70 649

27 086

4 449

492

7431

4463

Geneva

Haute-Savoie

Source : INSEE2012,BFS2015

SWITZERLAND

Home-work commuting - Greater Geneva

© MOT